Nalini Malani: “My Reality is Different,” National Gallery, London

Luisa Summers, September 25, 2023

Susannah, painted so beautifully. Her porcelain skin almost iridescent. Her elongated body bare and twisted towards her assailants. Her left hand hopelessly trying to draw the cloth around her, in a failed attempt to cover her pert, young breasts. The drapery covers her legs and genitals but leaves enough exposed to appear enticing and seductive. Susannah was a victim, but in art, she is always highly sexualized, as if it is her fault being so beautiful. Her face is frightened, her eyes are wide, and her mouth is wide open in shock. Her face is not disfigured in surprise, though frozen, distractingly desirable as the old men leer over her.

In Western culture, we have been raised looking at these images of sexual violence against women as if they are normal. The women are presented as victims, they never fight back, they never look unattractive in their shock or despair. The woman is an object for the male gaze, beautiful, untouchable in her painterly state, but tangible if the scene were to progress. Exposed for men’s viewing pleasure: lips parted, breasts bare, the tantalizing tease of what lays beneath the drapery. The viewer is encouraged to become like the old men in the scene, to lust after this beautiful girl, and in doing so, the old men’s violent acts are excused and becomes inevitable, becomes acceptable. Nalini Malani challenges us to look at these Old Master paintings in a different way. Speaking about her new exhibition, Nalini Malani: “My Reality is Different,” on display at The National Gallery, London, Malani states, “These paintings are not sacrosanct.” She gives us permission to question these works and how we feel about them. Which is not only welcoming, but liberating.

In Malani’s ‘animation chamber,’ the beautiful Susannah looms large on the wall, but before we have time to admire her beauty, she is covered in a red glow, reminiscent of bold, bright blood. The red glow covers her body only fleetingly while the leering old men are lost in the darkness; then the glow disappears and the men become visible, latching at her exposed, pale white skin. Susannah appears covered in red and black scratches, a large red ring circles around her hand suspended above the old man’s who is trying to pull away the drapery. Her face and head is covered with red and black lines as if her fears and thoughts are exploding. The use of this salient color presented in swift movements over the original artwork adds a sense of terror and urgency to the previously still and normalized scene. The men fade into darkness. Susannah becomes covered with a hastily drawn red figure, under which she dissolves, the red outline of a figure takes her place, rolling and kicking its legs against the thick, black background. Pain and violence is everywhere.

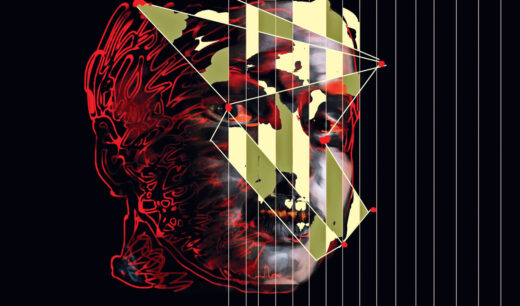

As the inaugural National Gallery Contemporary Fellow, Malani has transformed the Sunley Room into an overwhelming visual cacophony. Nine large video projections, playing on a continuous loop, fill every wall of the room, creating a fantastic panorama. Malani’s 25 striking new animations, hand-drawn using an iPad, overlap and interact with the Old Master paintings, all varying in length and endlessly changing the display and interactions. Projected among the imposing Old Master paintings are some of Malani’s beautiful, fictitious portraits of the marginalized. Giving a platform to those often excluded in the history of art, BIPOC faces are interspersed within the mix of classical white characters and fast-moving animations. All given equal importance, the BIPOC portraits bear witness as the moving, twisting figures and lines pull apart and highlight the most difficult details of Western visual history. Adding another level of intense and atmospheric detail, a layered audio is presented in the space alongside the juxtaposition of images. Making the experience truly theatrical, a strong woman’s voice, that of Cassandra, a prophet from ancient Greek myth, foretells her visions of the brutal fall of Troy, but is never believed. Voiced by Malani’s long-time collaborator and friend, Alaknanda Samarth (1941 – 2021), words from her monologue are echoed in writing across the walls of the gallery. Cassandra speaks her truth loudly within the space, she tells of the bravery of other women, she exposes their torture and death at the hands of men, she tells of the abuse done to her, her captivity, her rape, and the attempts to silence her.

“You will keep silent.”

“NO.”

(…)

“You don’t agree?”

NO.

“You will keep silent.”

“NO.”

Cassandra’s words ebb and flow in between strong drum beats, a ship sailing in a storm, the sound of the patriotic song, ‘Rule, Britannia,’ and a woman singing an Indian folk song. Malani accepted the fellowship on the provision that she be allowed to personally choose works from the collection for her project, and be allowed to ‘defile’ them. Malani’s selection of Old Masters included three from The Holburne Museum, Bath, and 22 from The National Gallery, London. The carefully chosen selections mainly concentrate on women and the feminine. Malani exposes the questionable details of the works, making the invisible visible through her interpretation and her ways of seeing. The scantily clad little girls, in Joseph Wright ‘of Derby’, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768, are distressed and terrified as they watch the life literally sucked from the bird. The precise chiaroscuro highlights these girls, gripping hold of each other in their terror, being comforted by an old man, but most shockingly with their dresses falling from their shoulders, for the seated child, dangerously close to exposing her undeveloped breasts. Her mouth is slightly parted in shock like Guido Reni’s previously painted Susannah, in Susannah and the Elders, 1622-3.

Malani’s choices challenge existing narratives and historical stories. Delilah has always been portrayed as the betrayer of Samson, a man perceived as mighty and herculean in strength. Malani questions if Samson is the victim, prompting us to rethink Delilah’s role, a woman whose very name means ‘delicate.’ The portrait of a black man fades, and is replaced with the skull from Harmen Steenwyck, Still Life: Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life, c. 1640. The viewer stares death in the face, but with the previous image still fresh in our minds, can we still see this as the vanities of human endeavors and pleasures, or death caused by the violence and control of imperialism and colonization? Colors and patterns flash and fade. Shapes and lines hide and reveal. Malani’s animations expose, cover, and share again, these questionable details. Without providing a specific narrative, Malani forces the viewer to look again at these works, and reconcile their own feelings. The long embedded European history of art is exhausted and regenerated by Malani, discarding the white male gaze to reveal overlooked and repressed histories. Malani gives a voice to the marginalized and especially to women. Through the artist’s unique interpretation, we experience history and art anew and realize that ‘My Reality is Different’ too. Nalini Malani: ‘My Reality is Different’, was on display at The National Gallery, London, UK, until 11 June 2023.