A YEAR IN ART: AUSTRALIA 1992

Mustapha , December 12, 2022

In 1992, Australia’s High Court reached a landmark verdict that dissolved the legitimacy of colonial rule. In siding with the Torres Strait Islander land-rights activist Edward Koiki Mabo, the court overturned the notion of terra nullius or, no-man’s land, which posited Australia as an uninhabited territory prior to Captain Cook’s arrival. Known as the Mabo Decision, the moment brought a centuries-long dispute to the forefront of socio-political discourse, igniting further conversations over suppressed languages, cultures, histories and generational pain of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

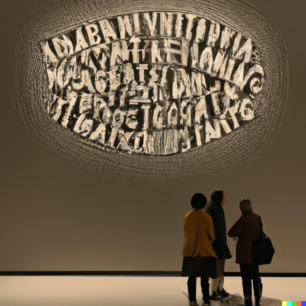

These conversations are at the center of Tate Modern’s A Year in Art: Australia 1992 exhibition, which spotlights the trauma of post-colonial Australia and its continued influence today. The free exhibition on the third floor of the Tate Modern is displayed in five rooms that trace the excruciating aftermaths of British colonisation in Australia. In the introductory notes, the Tate acknowledges that it has respect for “the Elders of these lands” and the “practices of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” whose cultural, spiritual, and artistic development is explored in videos, maps, photos, etchings, and paintings. Some pieces might be disturbing for some visitors as they show traumatic and extreme experiences such as isolation, enslavement, exploitation, and suicide that are the consequences of the colonisation.

After a 10-year struggle, Eddie Koiki Mabo, a Meriam man, obtained his people’s ownership of Mer Island (Murray Island). The Australian government recognised the traditional inheritance system of the land and Aboriginal land rights. Mabo died on June 3, 1992, and this day is commemorated yearly and called Mabo Day.

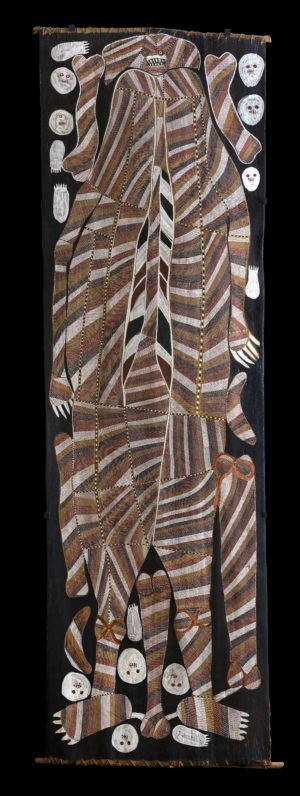

Mabo’s hand-drawn maps that are on display indicate a profound understanding of the territory that is perceived as a living element and that together with humans, animals, rocks, air, plants, and soil create cultural identity and sustain all creatures. Aboriginal people do not own the land in the Western sense of the word, but they feel responsible for it and care for it. The devastating consequences of colonisation are therefore not only visible in the history of the deportation of people, in dispossession, imprisonment and enslavement; they also threatened the environment, causing spiritual and physical damage. The colonisers ignored the cultural legacy of Aboriginal people that is disseminated all over the territory. Their hunting, fishing, and gathering practices are depicted in rock paintings, and their deities, legends, and folktales are represented in cross-hatch paintings.

The work of John Mawurndjul testifies to the merging of old and new in which ancestral figures depicted with the traditional cross-hatching technique in lines of ochre and red perpetuate the tradition and resist erasure. All the works on display give a personal and political response to the privations and injustices of British colonisation. They expose the appropriation of the land by the colonisers and the use of Aboriginal peoples as commodities. The thousands of convicts deported to Australia, though some of them became landowners eventually, were considered commodities, too. Convicts and Aboriginal peoples are absent in commemorative paintings that celebrate the conquest of the land by Britain, such as The Founding of Australia 1788 (1937) by Algemon Talmage. The territory was indeed considered terra nullius, that is, a land belonging to nobody.

This kind of narrative is severely criticised by Gordon Bennett in his painting based on Samuel Calvert’s 19th century etching featuring Captain Cook taking possession of the Australian continent. In Bennett’s painting, the background has the colours of the Aboriginal flag – black, red and yellow – in geometric forms that are a reminder of Malevich’s square; it is a void that refers to the suffering caused by colonisation. The artist’s series of etchings, How to Cross the Void, analyses these issues more deeply and from different angles. The disturbing and tragic consequences of the white man’s domination, such as rape, the deaths of black people in police custody, and the erasure of Aboriginal culture, are depicted in thought-provoking pieces that overturn the legitimacy of the ruling society.

Other artists, such as Kame Kwgwanege, focus on representation of the environment. The technique of using overlapping dots is intended to include soil, air, vegetation and animals in a comprehensive mapping of the land. Environmental and political issues are also present in Dale Harding’s The Leap/Watershed 2017, which uses the technique of blow painting present in rock art and commemorates the death of about 200 Aboriginal people who were forced to jump off a cliff to escape the police.

Judy Watson emphasises community work. Her series of sixteen etchings on paper, a preponderance of aboriginal blood (2005), challenges discrimination against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The pieces are stained in red, representing blood, on a background of copies of electoral registration forms that classified people according to race. Aboriginal peoples were not allowed to vote until 1965 unless they had a white parent.

The outback is depicted in a thought-provoking way in Tracey Moffatt’s photographic series Up in the Sky (1997). Her apparently simple narratives highlight the isolation but also the violence of the scenes as well as the characters’ sense of loneliness. Sudden moments of vitality alternate with displacement, both of which are present in the lives of Aboriginal peoples and white peoples.

In the last room, Helen Johnson’s work explores the legacy of British colonisation. She is a non-indigenous Australian, and her critique focuses on what she calls “Australian rotten foundations” and the enduring colonial connections with Britain. Her acrylic painting Bad Debt (2016) shows the huge damage colonisers made to the environment by introducing new animals, such as foxes and rabbits. Seat of Power (2016) satirises the connections with British power, using literal and symbolic images such as the British House of Commons sketched on a background that features the Speaker’s Chair.

The exhibition exposes in a dramatic way the damage that British colonisation caused to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and to the environment in Australia. The artwork on display deftly shows the struggle of the people of the land not to be erased physically, culturally, and spiritually. Their legacy endures in traditional artistic practices that confirm identity narratives and the connection with ancestors, and they grant survival. They oppose the cultural homogenisation and the imposition of Westernisation by the imperialistic power that dominated since British colonisation.

The Tate Modern

Through to Autumn 2022