Arlene Wandera, Artist, conversation

Kenyan born artist Arlene Wandera moved to the UK with her family at a young age. Since obtaining her degree from the Slade School of Fine Art,London, she has gone on to participate in numerous exhibitions and projects in the UK and internationally. Most notably, she represented Kenya in the 57th Venice Biennale and participated at this year’s Dak’Art Biennale. She is also one half of the collaborative duo Duck & Rabbit Projects. In this interview, the artist gives us a glimpse of how she arrives at her art, her inspirations, and aspirations.

INTERVIEW WITH ARTIST, ARLENE WANDERA

Your art includes sculptures, installations, photography, drawing, sound, and performance and you don’t wish to restrict yourself to a single medium. Having said that, have you found that certain ideas/artworks are better suited to certain mediums? How do you negotiate with what would be the best format for you to convey your message?

I think of myself as a maker, so this already determines how I begin the process of investigating ideas. The initial stages of working through an idea involve intuitively selecting objects and materials that feel right to start playing around with.

This is followed by the process of elimination and really thinking about whether the work can be articulated using a different medium. So, when an idea requires working with sound for example, a medium that isn’t necessarily familiar to me, I usually like to do further research and also seek advice from professionals in the field. I prefer to be hands-on and learn about the process and techniques needed to produce an artwork. Sometimes that isn’t realistic or possible, so a collaborative approach is something I also engage with.

How different is it when you are studying art as a student and later when you take it up as a profession? With the constantly evolving art scene, a landscape where new mediums/formats establish themselves as art each day, how do you think the academic space should adapt to produce artists/creatives?

I think learning is a life-long activity, and to a certain extent the line between being a student and a professional becomes blurred in that respect. Having said that, both time and practice are vital ingredients in sharpening and honing one’s creative abilities. What I have noticed about my current practice compared to when I was studying at the Slade School of Art is that I am able to explore ideas with more direction and more efficiency.

I also think that the academic spaces and institutions (particularly in London, as this is the space I occupy) are adapting to the ever evolving art scene that embraces new mediums and formats.

In a post-colonial world where writers like Frantz Fanon and Ngugi wa Thiongo have elaborated on the identity crisis faced by people whose own cultures are wiped out by the coloniser’s culture, you have often seemed to derive strength out of your liminality. How does this realisation feature in your artworks?

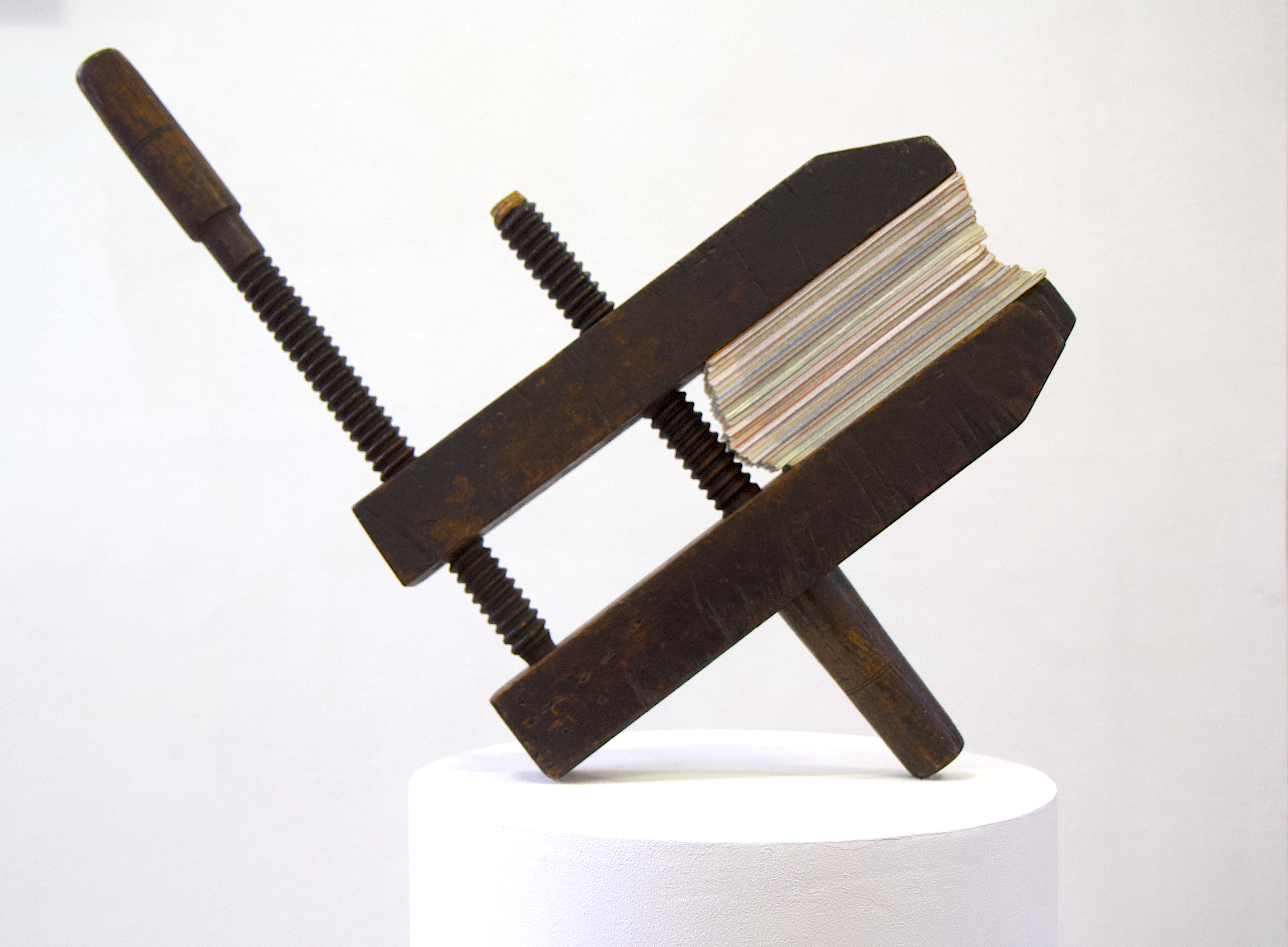

Being born in Nairobi and then being raised in the UK was a choice made for me by my parents. That choice created a space for me to occupy two cultures both in my personal life and in my practice. I embrace the duality and accept it for what it is, and I think it’s a beautiful thing. One that makes it effortless to derive strength from. So within my practice, it makes sense for me to combine western sculpting techniques with the repurposing techniques I learnt in my childhood to make the toys I played with.

In our effort to rid ourselves of binaries/categories, it seems like the 21st century has come up with even more labels. Do you ever feel bogged down by the expectations people might have from you/ your art due to your racial/gender identity?

No, not really. I am only concerned with the labels and expectations that I create for myself because external labels and expectations can be a dangerous path to travel when making art. It is important for me to inhabit a space where I have the freedom to engage with my imagination and ideas and also use that space to constantly challenge ideas.

How much has the Kenyan art scene changed over the past decade? What do you think the future holds for Kenyan artists in an environment that is encouraging global participation?

As my practice is based in the UK, my engagement with the Kenyan Art scene is currently rather limited. Having said that, Nairobi has the space to critically engage with contemporary art in a dynamic way. Recently, I have found myself engaging with more peers based in Nairobi, so my plan is to return there for a few months to figure out the lay of the land (art scene-wise), engage with artists and simply create.

Pic Credits: James Muriuki