Artist, interview, talent

Annabel Abbs is a multi-award-winning writer of fiction and nonfiction, published internationally in 30 languages. She grew up in Wales and Sussex, with stints in Dorset, Bristol and Hereford. Daughter of academic and poet, Peter Abbs, she has a degree in English Literature from the University of East Anglia and a Masters from the University of Kingston. She lives with her family in London and Sussex, and is a Fellow of the Brown Foundation.

In Conversation with Annabel Abbs

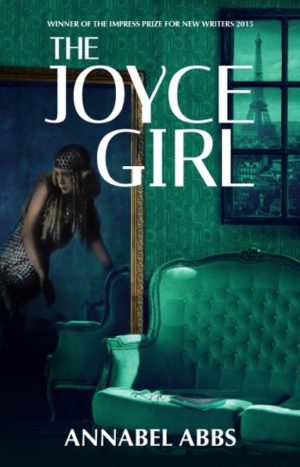

I’d long been looking forward to meeting Annabel Abbs, author of the highly acclaimed and widely translated The Joyce Girl (Impress Prize 2015). Abbs’ powerful portrait of Lucia Joyce’s struggle to free her artistic passion for movement from her father’s shadow can’t fail to grip anyone with a dream in their head. Joyce, Beckett, Jung – there are many important men in this book – but what sets it apart is the second genius in the family – a woman of talent and ambition whose dreams are denied her.

AB: Annabel, fantastic to talk to you today. Lucia’s fury at the waste of her talent is startlingly real. What made her story so essential to tell?

AA: When I first came across Lucia’s story I was horrified that many of the men in her life became legends, while she, a talented dancer, was confined to a mental asylum. It seemed to be a metaphor for what happens to many extraordinary women – historically and today. Women may not live out their unfulfilled lives in asylums any more but they still face huge struggles combining artistic endeavour with family life, or achieving recognition in more patriarchal cultures.

The image of Lucia languishing in an asylum also served as a metaphor for the many creative females who’ve been overlooked and forgotten. Publishers like Persephone and Virago have done a great job of returning female literary voices to us, but the ‘canon’ still only includes the usual suspects: Eliot, Austen, the Brontes, Woolf. The world of visual art is no better and yet women have been successfully painting for hundreds of years. It’s important that we look back and see ourselves as part of a long lineage of female artists. This means rescuing forgotten voices from the shadowlands of history and remembering those who tried and failed.

I think the shadow of great male writers, like Joyce and Beckett, still hangs over us all. The Irish Times triggered a huge debate on this subject recently when John Banville was reported as saying no writer could be a good father. The hundreds of replies were testament to the forbidding myth of the genius writer – the tortured soul at the mercy of the muse, locked away in his (sic) bohemian garret. That model doesn’t work now but the myth lingers. In The Joyce Girl, I wanted to show the fallout of that myth.

AB: What would you say to the argument that the world has moved on – that women are just people, that focusing on the past is not productive?

AA: In many ways the world hasn’t moved on. The Joyce Girl will soon be published in Turkey, a country where the rights of women have regressed. Meanwhile, the increasing nationalism we’re witnessing has overtones of the 1930s. I think historical fiction plays a vital role in illuminating darker periods of history, but from a safe place. There’s been a lot of press about why the Costa shortlists were dominated by historical fiction. I believe it’s partly because many of us want to escape from the current world, but it’s also because we’re looking back for answers. Historical fiction offers us both in one package – a chance to escape and an understanding of how we got to be where we are.

AB: Why did you choose to write The Joyce Girl as biopic fiction rather than straight biography?

AA: I love the genre of biography but it can’t explore the inner life of its subject in the way that fiction can. It was the inner life, the emotional truth, of Lucia that fascinated me. Even if I’d wanted to write a biography of Lucia, it would have been impossible. She was effectively wiped out of history when her letters, poems, medical and psychiatric records were erased. The remorseless way in which her voice had been muzzled was partly what attracted me to her story and it’s still very topical. Every week we hear about attempts to destroy records or evidence in order to frame things differently. This is how history has been constructed, usually by the victors wishing to present a particular image or story line. I wanted to raise this issue through the story of Lucia.

Today we have the internet and social media, very sophisticated but equally very malleable tools for determining how facts are presented. So the treatment of ‘facts’ is more relevant than ever before.

AB: What did you learn from writing about James Joyce and Samuel Beckett?

AA: I’ve never been on a writing course, so writing about two writers was very helpful. Ulysses is almost a masterclass in writing, because Joyce experiments with so many different forms of narrative. I was able to take the styles that worked and ignore the rest. I still have paragraphs from Ulysses on the wall above my desk. But what I really learned was resilience. I read all the biographies of Joyce and Beckett: they believed in themselves, they never went on writing courses (!), they suffered innumerable rejections (including censorship) but they never gave up. Every time I felt defeated I reminded myself of their stamina. Then I got back to work!

AB: Writing courses have become increasingly expensive. Other than learning from Joyce and Beckett, how did you write a novel without attending one?

AA: I read constantly. I have one writing exercise that I did and still do. I noticed that my artist friends spent a lot of time copying the artists they admired. I started doing the same. Whenever I came across a thrilling piece of writing, a gripping opening, a brilliant character portrayal, I’d copy it out, long hand. Then I’d type it up, playing with the sentence structure or the punctuation or the language to see if I could improve it, which invariably I couldn’t. After that I’d rewrite a section of my novel in the same style or tone. Then I’d throw it away. That was how I finally found my ‘writing voice.’

But as a debut I found writing without the support of fellow writers difficult and lonely. It takes considerable self-discipline too, so I don’t necessarily recommend it. Competitions were critical, both as deadlines and as a means of getting feedback. I’m a huge fan of writing competitions and the incredible people who organise them.

AB: Tell me, how can a novel like Ulysses be simultaneously regarded as the best in the English language and the hardest to read?

AA: It’s not the best, but it was very radical for its time and it changed the course of literature. It’s hugely inventive, brilliantly observed and still very relevant. Its exploration of what it means to be an outsider seems particularly pertinent at the moment. Finnegans Wake is much harder to read than Ulysses – I’d say it’s unreadable. Personally, I like a book with a plot so I’d never sacrifice readability for linguistic invention. However, Eimear McBride (who I consider Joyce’s true successor), managed both in her brilliant A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing.

AB: Interestingly Eimear McBride’s books are not seen as ‘women’s fiction’. A lot of readers and writers find this term frustrating – why should books by women or books with female characters so often be differentiated from the mainstream when women make up half of humanity?

AA: I agree – it’s infuriating. Why is there no ‘men’s fiction’? I suspect this is partly to do with the economics of publishing. Women buy and read many more books than men. To make life easier, publishers have created a category of ‘women’s fiction’ but it’s seen as less literary, less worthy. Where female writers have overcome this, it’s often because they’ve written about men: would Hilary Mantel have achieved the same prominence if Wolf Hall hadn’t been about Thomas Cromwell?

On the other hand, there are some fantastic female publishers, like Honno, enabling female writers to have a platform they might not otherwise have.

I actually think men are more open to so-called ‘women’s fiction’ than is often implied. I get more letters about my novel from men than from women, but the reviewers of it (on GoodReads and blogs) tend to be female. That suggests to me that men are reading books about women but not necessarily going public!

AB: Going back to fury, we have recently seen record turnouts at Women’s Marches across the world, with Donald Trump since living down to expectations. I know you marched in London – is writing stories relevant to politics?

AA: Literature is essential if we’re to combat extremism. The writing, reading and dramatization of stories are the most effective ways (I think) of increasing empathy, improving diversity, creating a more humane world. Only by slipping inside the skin of other people can we understand what makes them human. Our imagination gives us a route into the future as well as the past. Possibilities of every sort can be explored. I’ve been imagining a world controlled by people like Trump – and it’s frightening.

The Joyce Girl by Annabel Abbs is published in the UK by Impress, was a Guardian Reader’s Pick 2016 and has been longlisted for the Waverton Good Read award.

Alice Burnett’s first novel, Ideal Love, will be published by Legend Press in August 2017. Alice grew up on a farm in Devon, England, studied maths and philosophy at Cambridge University and worked as a lawyer in London and Paris before taking up writing. She lives in London with her husband and three sons.